Are you one of the millions of Americans putting in extra hours at work but not accomplishing more?

It turns out most of us are. Recent research suggests Americans are only productive for about 45 percent of an average eight+ hour workday.

Lately, we’ve seen companies across industries championing a number of work-life programs to support workplace mental health and a corresponding increase in spending on corporate wellbeing programs—$40B in 2018. Yet it’s not unusual for employees to spend 50-60 hours a week working—40% of professionals now work over 50 hours a week—and in the gig-economy, that can rocket up to 100 hours a week. In my industry, tech workers tend to put in the longest hours. So it’s not a surprise that across the United States, employees are taking 15% less vacation time than they did 20 years ago.

But why? And it is worth it?

There are plenty of reasons to stem this tide. Employees that work more than 11 hour days are 2.5 times more likely to develop depression, and 40-80 times more likely to develop heart disease. And women who put in long hours have been found to triple their risk of developing chronic and acute diseases including diabetes, cancer, heart disease and arthritis. In the US, stress alone can cost businesses over $300 billion a year in health care expenses and missed work.

The 40-hour workweek dates back to Robert Owen, a Welsh labor rights activist who split the day into “eight hours labor, eight hours recreation, eight hours rest.” His theory never caught on in Europe, but President Roosevelt’s administration picked it up in response to exploitative working hours during the Great Depression. His New Deal Economy ushered in both a standard 40-hour working week and a fair minimum wage, adopted under the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938.

Another significant reason to rethink our current approach to how many hours we work a day, is how many years we will need to work. My parents’ generation worked full time for 40 years before retiring. I am a GenX’er, I’ll work full time for 50 years before retiring. I have kids who are both young Millennials and old GenZ’ers, they will work full time for 60-years before retiring. Overall, on average, as a species, humans are living longer healthier lives (50% of babies born today in North America will live to 105), but global pension programs will not be there to support growing percentage of our retired population. So not only do we get to work for more years, we will have to work for more years. Given this wonderful longevity, we need to pace ourselves. We get one body—can it work 50 hours a week for 60 years?

As someone who thinks, writes, and speaks about the future of work, I’d like to challenge our assumptions about continuing to follow this practice. In Europe, countries and companies have been adopting new standards around the work week to allow for new growth in a modern economy. France led the charge for shorter workweeks in 2000, dropping to 35 hours. Since then, 10 other European countries have followed with work weeks ranging from 29 to 36 hours.

Opponents to shortening the work week argue that this type of economic thinking can reduce competitiveness, increase staffing and management costs (particularly when 24-hour staffing is required), and further complicate a patch-work system of benefits and social supports. So what benefits can we learn from Europe’s experiences?

Boosting morale is not only good for your productivity, but also for the level of work and increased customer satisfaction.

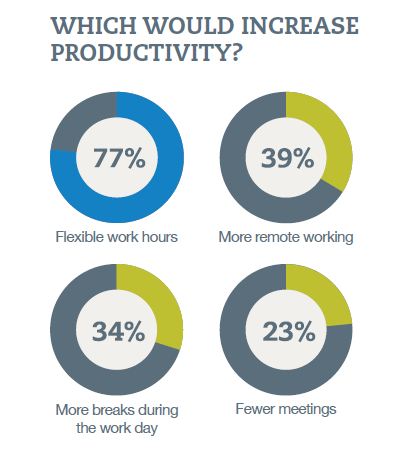

Countries who have found success with their programs, as well as those who advocate for others to adopt them, cite a number of benefits. Shorter working hours show improved recruiting, allowing businesses to be more competitive and reel in the most talented workforce. At a macro level, a shorter work week is part of a larger discussion about the changing workforce that includes flexibility of all kinds. A study by Bentley University revealed that 77% of millennials say flexible schedules would make their workplaces more productive – and what we know to be true is that millennial voices are shaping the future of work. There are also resulting health problems when employees work long hours. Studies by Marianna Virtanen and colleagues at the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health have confirmed these issues and found that additionally, long working hours impact a company’s bottom line in the form of absenteeism, turnover rates, and rising health insurance costs. Additionally, results of a study by Liana Landivar at the University of Maryland Population Research Center, show that countries with shorter work weeks have less hour-inequality between spouses, supporting the idea that shorter work weeks can encourage more equitable work distribution of unpaid work, ultimately shrinking gender gaps.

An unexpected benefit to these staffing solutions has been the environmental impact. Across countries who have shorter average working hours, the carbon footprint is also found to be smaller. Preliminary studies show that a reduction in working hours can result in one-quarter to one-half of global warming.

At least one US company has dipped a toe into the shorter workweek: Basecamp enforces a strict 32-hour work week during “Summer Hours” (May through September), which they find to result in a culture that not only draws top talent, but also ensures lower turnover rates due to loyal employees. As these experiments continue around the world, it is worth asking ourselves, how are our current policies serving us, and why is it so hard to break away from the past?

Boosting morale is not only good for your productivity, but also for the level of work and increased customer satisfaction—and happy and healthy employees mean a happier and healthier bottom line.

excellent questions and stats. Here’s a quote I like: Work should be more fun than fun – Marilyn Moats Kennedy, career and workplace strategist. If it is, then the hours don’t matter. But if it’s in endless meetings, being and feeling less than productive, then surely a shorter workday/workweek could lead to greater productivity and enhanced work-life balance. We need to make the very best of the hours we do work, and be ready to stay when needed and go when needed. The latter does not happen often enough.

I like the report